Review: Twenty-One Years Young by Amy Dong

It is this appeal to the universal within the stunning rendering of specificity that makes Twenty-One Years Young such an enthralling collection. As Amy Dong is unabashedly vulnerable in her storytelling, I feel safer in embracing my own narratives as I reminisce and lean into my continuing coming of age.

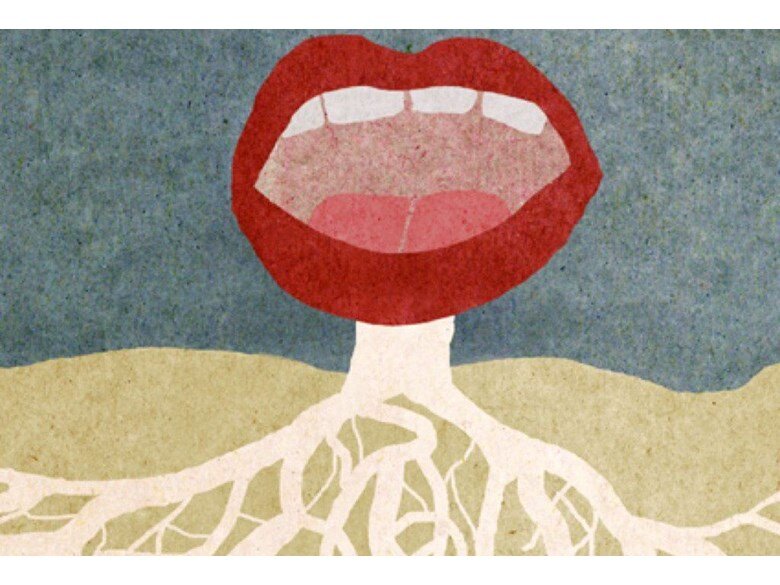

Black Rose

What could have caused such a grotesque deformity?

I always answer you

in a language you refuse to hear,

from roots you try to curse,

with beauty you fail to acknowledge.

Language 4R and Mix-Placed Roots of Selfhood: Conclusion

Everyone grapples with questions of belonging at some point in life. But for me and perhaps other African Americans, these questions are like concrete. They pave manicured and gentrified roads. They make up the walls of overcrowded prisons. They symbolize progress while simultaneously shrouding it with doubt. And to make matters worse, or at least more complex, I struggle to call the very language I use to answer these questions my own, adding yet another layer of uncertainty. I still do not know if African Americans have a true mother tongue. The issue remains unresolved. But I do know that African Americans have roots in both African and American soils and that there is a remnant estrangement from both by distance and pain respectively.

Language Restoration: Ancestral DNA Testing and Links to Language Legacy

Ancestral DNA testing has sparked international fascination. People are enthralled by DNA testing’s scientific contribution in defining their lineage narrative. Family stories of movement and historical records can be fortified by this biological analysis. But for the African American community, ancestral DNA testing has an even greater responsibility; it combats the historic erasure of African American lineage by indicating explicit genetic links to African shores. Ancestral DNA results do not provide a narrative that is as comprehensive as Alex Haley’s legendary novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family, based on the author’s traced lineage back to the African continent. Yet, genetic testing can be a very crucial starting point to restoring a coherent ancestral identity.

Language Reclamation: Gullah Language and Creolization with African Roots

When I was a child, I used to love watching reruns of a show called Gullah Gullah Island. It was about a family who lived on an island off the coast of South Carolina with a giant yellow tadpole named Binyah Binyah Poliiwog. And though five-year-old me was probably most intrigued by the giant yellow tadpole, I also marveled at seeing people who were African American like me speak another language. Alongside presenting lessons on friendship like other children’s television shows, Gullah Gullah Island was also centered around teaching the Gullah language and demonstrating the intentional maintenance of African traditions on the island.

Language Reappropriation: African American Language and Diasporic Identity

Classification is often necessary in forming the basis of discussion. Concepts develop in relation to other pre-existing concepts, and classification maps out these dynamics for the sake of organization. However, classification is hardly ever a neutral process; it is almost always shaped by power. Consequently, the line between beneficial classification and toxic hierarchization is dangerously thin, especially in the comparative analysis of diverse human behavior and culture. Linguistic classification of communication modes is far from impervious to the influence of hierarchized superstructures.

Language Reparation: African American English (AAE) and the US Education System

I still cringe whenever I recall my grammar policing days. I was well-intentioned, but admittedly obnoxious. Unbeknownst to me, I was actually acting out of a place of misinformed ignorance. The education system in my area conditioned me to haphazardly conflate the bad or incorrect uses of Standard English (SE) with the linguistically legitimate grammar structures of African American English (AAE) that some of my peers and loved ones used.

Language 4R and the Placement of Roots: Introduction

One’s mother tongue is one’s language of intimacy. Perhaps it carries tender childhood lullabies. Perhaps it paints one’s dreams. Perhaps it swells with anger. Perhaps it wrings out one’s grief. A mother tongue shapes one’s perceptions of the world and of oneself. For better or for worse, it provides a means of communication and a sense of place.But what if each word of your mother tongue reminded you of the violence your ancestral mothers endured? How much of that violence would seep into the way you see the world and yourself? Can a language that holds such a legacy of violation ever be your language of intimacy?